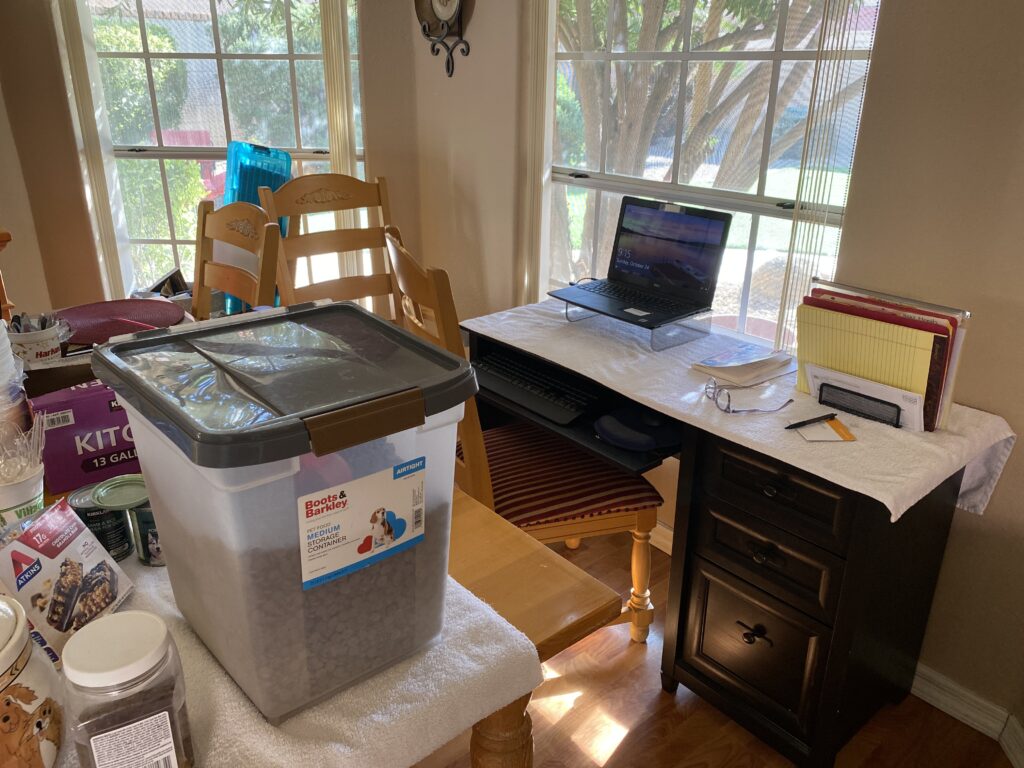

Behold the “Work In Progress,” fondly known in the writing community as the WIP. A million ideas crammed into digital folders and old-school file drawers. Half-started, almost-finished stories and essays and collages and poems.

I have written before about unfinishing, about how we are all works-in-progress. And if my current WIP count is somewhere between 60 and 100, then I say: whatever. Rather than beat myself up over lack of completion, I choose to embrace the wellspring of inspiration that flows between places and moments, a yoga mat, the pen, a candle, the sea, the desert.

I used to believe the WIP folder was where dreams went to die, but now I see how works in progress lead to words in progress and eventually, words in print.

I have also come to appreciate the effervescence of these projects. My writing and art—completed or not—is a reflection of my real self. With a tug of my ancestral threads, I fashion a patchwork of the writers and artists who went before me: grandfathers, a grandmother; uncles and aunts; my mother, my father.

And as I occasionally share some of these creative scraps, I invite you to join me in celebrating the unfinished as we view progress through the imperfect lens of reality.