Thanksgiving should be all about gratitude, especially this year. My husband and I have both made it this far, healthy and COVID-free; my parents are healthy, even in their locked-down care homes; the desert finally cooled down enough to light a fire after the big meal; the entire Thanksgiving feast—turkey breast and stuffing, my mother’s famous squash casserole and cranberry pie recipes—all came out perfect. In a perfect world, prime conditions for gratitude. Right?

Over the past two years, though, the holidays have not been perfect for us. My husband spent last Thanksgiving in the ER, battling an infection that rendered him immobile for nine months. The Thanksgiving before, we lost his only child to a tragic suicide. And this year, in a somber confirmation that the spread continues to plunder the lives of families everywhere, we learned on Thanksgiving Eve that his brother, sister-in-law, nieces and nephews have all tested positive for the virus.

So. Let’s talk about the other “G” word. Grief.

Sometimes, I’d rather carry the heaviness of grief than feel the grace of gratitude. For six years of caring for a mother with Alzheimer’s, I’ve experienced a cornucopia of grief. Grief at the loss of her identity, at the loss of her abilities as a talented artist. And through her recent struggles with speaking.

When the pandemic hit in March, I had just said farewell to my parents back east—my mother safely returned to her memory care home after surgery on a fractured hip; my father living in the first days of quarantine and lockdown. The cold reality of a baffling virus and two dozen infected residents in his senior community left him frightened and depressed.

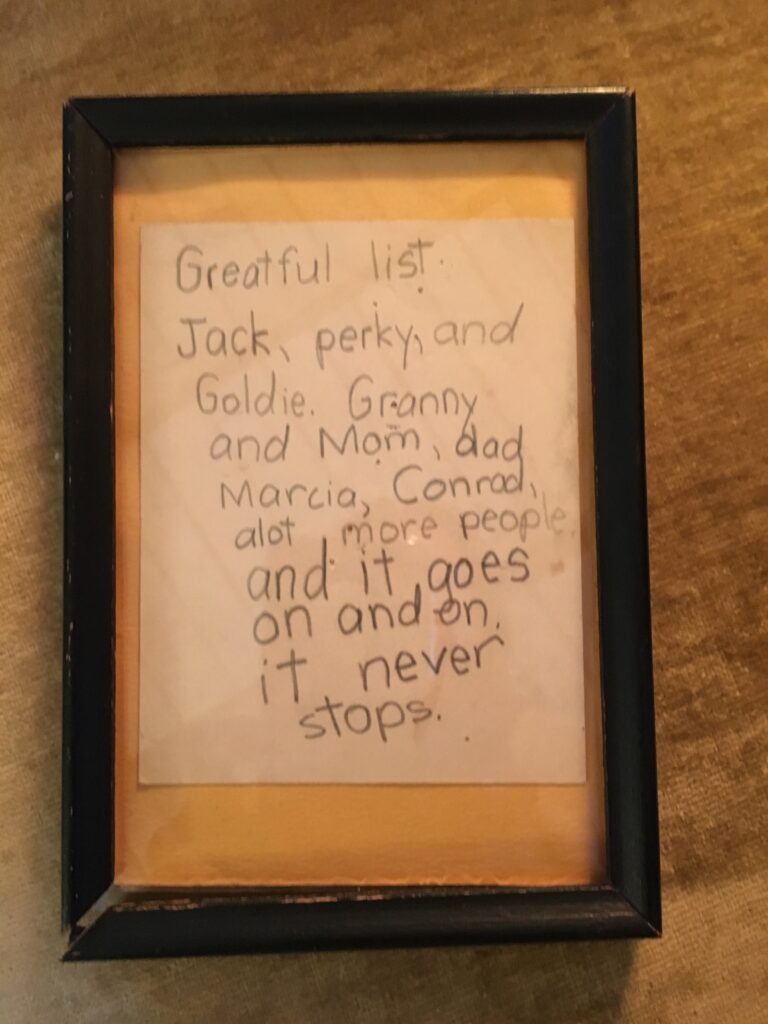

At first, I wore my father’s despair like a cape, my shoulders slumped and listless. Later, I found myself grateful for the blissful oblivion dementia had granted my mother. And I heard her voice from the days of my childhood, when she’d redirect my sullenness at doing chores, or my complaints about my allowance and ask me: but, sweetie, what are you grateful for?

And so, what began as a challenge to my father in April has continued now for eight months: each night, we text each other three things we’re grateful for. They don’t have to be monumental, I tell him. It can be a sunrise. Or the sparkle of sunlight on the waves. The blueberry muffin the staff leaves outside your apartment every morning. A new pair of running shoes.

Yet the pandemic marches on, the world collectively sharing its grief. “That discomfort you’re feeling is grief,” says a beautiful article I stumbled upon recently in the Harvard Business Review. “We feel the world has changed, and it has. We know this is temporary, but it doesn’t feel that way, and we realize things will be different. The loss of normalcy; the fear of economic toll; the loss of connection. We are not used to this kind of collective grief in the air.”

Alas, there is no statute of limitations on grief, and we all grieve differently. But in the nightly glimpses of gratitude shared with my father, I can take a brief holiday from grief.