Monday

Dawn. I’m walking the dogs. Across the street, a coyote on the sidewalk.

A Navajo saying holds that if a coyote crosses your path, turn back and do not continue your journey. The coyote is an omen of an unfortunate event or thing in your path or in the near future.

We did not turn back. Our journey continued.

“I wouldn’t wait two more weeks,” says Johanna, the director of my mother’s memory care home on the phone 30 minutes later. “Get your second shot and we’ll see you Friday.”

Should I call mum? Tell her I’m coming? I text Johanna later. Will she even comprehend?

No need, comes the response, as immediate as the remaining time my mother has on this earth. She smiled when we told her you were on your way.

Wednesday

Halfway through my workout, killing time before the needle is jabbed into my arm, another call. “She’s had some sort of neurological event. She’s non-responsive. Get your shot and fly out on the red-eye tonight.”

11:58 pm: wheels up.

Thursday

Somewhere between midnight and 4 am and a change of time zones, I sleep. Restlessly, the sleep of dogs, legs flailing, waking myself up with a low moan, I was leaping, in that twilight sleep, limbs clawing uselessly at the air, the landscape unclear, only the starry parallel universe of deep blue. What if heaven isn’t white, but only darkness? Would there at least be stars?

5:30 am, Philadelphia airport layover. A layer of sticky invisible grime and despair coating everything, even the air.

Friday

Everything I bought at Reny’s department store yesterday smells like old ladies and bathrooms. Bubble bath. Deodorant. A sweater. Everything.

The ride to my mother’s takes 30 minutes, in a rental car reeking of a thousand miles of nervous sweat and stale cigarettes, neither of which are mine.

In her room, the odor of old age and death. In the background, classical piano music soft and sweet. Today she is in the recliner in her room, propped up by so many pillows she’s almost hidden from view. Eyes closed. Cereal stuck on her speckled sweater, the frosted flake like the age spots on her thumb.

These hands, I say, twining her pale, liver spotted fingers through mine. These hands are strong and powerful. They bake pies and sew dresses and sketch flowers and make music and write worlds of words. And when I am sad or tired or scared, they hold me.

These hands are the best hands, I tell her and she whispers back: Best in town.

For lunch, I feed her homemade cheddar and mac. “Kinda plain,” she says, ever a gourmet cook with discerning tastes.

Caregiving, I think, is as lonely an existence as being an only child. Like being alone in your head with dementia. Outside the biting wind tears through the woods, swirling at the window’s edges as if it wants to rip out these last pages of our lives.

Saturday

Hailey, the house cat, and I peer out the window. A few buds have sprouted atop spindly tree branches. The bay, blue and rippled. I talk to fill the space, too much of both, and it doesn’t register, her eyes still shut, sticky with sleep or death or a little of both and we make an agreement. It’s okay to let go, I tell her, we can both let go. God’s got our backs. She is silent, unresponsive, then grips my hand with the strength of a wrestler, and asks: how long? How long is the door open?

The door is always open, mum. Whenever you’re ready just step through. It will never close; the essence of you will linger until, when I’m ready, I’ll walk through to meet you.

Sunday

She’s not able to chew or swallow, Erica says. Just juice and water.

Could I give her ice cream for lunch? I ask. She could just let it melt and taste its sweetness.

And so, I give her a tiny bowl of ice cream, black raspberry. Her favorite flavor and it reminds me of Casey, my golden retriever of fourteen years–the closest to a son I’ll ever have–and how he ate Reese’s peanut butter cups on his last day on earth because chocolate was finally okay.

Now, in this bittersweet moment, I am angered at death’s incongruity, at this false spring which went from 50 to zero in 24 hours. And of the universe I ask only one thing:

If seasons and temperatures can move backward, why can’t my mother’s last moments on earth roll back to the days where black raspberry ice cream for breakfast was but a decadent tradition all those Augusts ago and not spoon-fed by a sobbing daughter?

Monday, redux

For my mother this morning, I weave the tale of a perfect summer day. A picnic at the beach, ice cream cone in town, strolling past her paintings on display at the art show on the library lawn, then home for iced tea on the porch, mint leaves from the herb garden, crab rolls for supper, gentle breeze blowing through the green gingham curtains she sewed so long ago.

She has been silent for hours, days. Eyes still closed. It’s okay, mummy. Everyone is okay. I’ll take care of everyone. And she whispers: do you…promise?

Yes. I promise.

Tuesday

Each day her breath is more jagged, and each day she melts further into her easy chair, but she is uneasy today and restless. Her skin, cool to the touch. The odor of illness seeps from her pores and each day, I carry it with me, embedded in my flannel shirt, my hair, absorbed into my own skin.

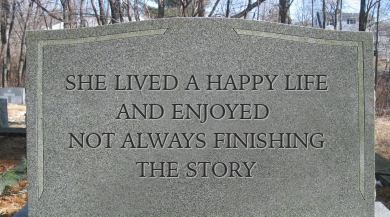

Everything I write lately is followed by a question mark. Every word, project idea, line of a story, all question marks.

Which will run out first? The pages in my journal or my mother’s breath?

Wednesday

Today, she is in bed, tinier than she was yesterday. Her bony limbs at all angles. Awkwardly, I fold my bony limbs to fit onto her bed and we’re just two skinny girls spooning on a single bed. Together, we lie all day, and as I continue to recite the prayers and hymns from my childhood that now plague me inexplicably in their entirety, dusk steals the light from the sky. Outside, the sun sinks below the bay. One last time.

I am uncertain whether to stay and witness her last moments or leave with this final heart-sweet memory.

Tomorrow, when the grief unspools, and logistics of death begin, I’ll unpack the suitcase of her life. But tonight, I’ll be alone with her, before the world finds out.

Thursday

My mother passed early this morning and suddenly I realize there is nothing left to paste into this scrapbook of a life.

I am frozen in place, going through the motions of the morning, a kaleidoscope of emotion, a bastion of numbness. I had a week with her, a week some might not consider beautiful but for me, it was.

Time’s passage has been inconsistent, compressing and expanding, its breath as unpredictable as my mother’s own.

Time yielded and I saw her through the lens of my childhood, the young mother tending to my much younger self and then, when time drew nearer, I saw my grown self through the lens of reality, a mother bringing her child safely home.